20 | Barbarian

2022 was a ripe year for the horror genre, with a healthy mix of genre mainstays making their way back to multiplex screens and new, original films to keep devotees on their toes. Personally, I can’t think of another film this year that came so out of the blue to dominate the box office, relying on word of mouth, a secretive marketing campaign, and a title that at first glance has more in common with Eggers’s The Northman than the film. In that same spirit, I’ll only say that Barbarian’s premise is built sturdy, with two mutually suspicious strangers brought together under the less than ideal conditions as someone, or something, lurks in the basement below them. The cinematic equivalent of a funhouse, Barbarian settles you into the familiar genre conventions before turning out the lights and switching things around, misdirecting and confounding its audience, all while comfortably seating them on the edge of their seats. While there’s certainly something to be said about its thematic concerns of toxic masculinity and the reverberations of it, Barbarian works as well in the subtle notes as it does building up to the grander reveals, and with a director that’s a veteran of comedy, there’s an odd humor to the whole affair, culminating in one of the great needle drops of the year. – N.A.

19 | This Much I Know To Be True

Nick Cave and Warren Ellis are the greatest artists of their time.

This film proves that. – C.W.

18 | Top Gun: Maverick

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the year was the overwhelming competency and emotionalism of TRON: Legacy director Joseph Kosinski’s Top Gun reboot. I suppose we should’ve seen it coming – Tom Cruise’s tightly-controlled management of his own brand has prevented him from starring in anything worthy of less than a solid B+ for the last 10 years, and Christopher McQuarrie’s involvement as a cowriter and producer certainly indicates a base level of action film proficiency – but the film’s absurdly massive box office success and equally rapturous critical response still managed to shock given the project’s initial appearance as just another lazy, overly-obvious piece of regurgitated corporate IP. Against all odds, this is a Real Movie: that first giddy training montage set to “Won’t Get Fooled Again”; Val Kilmer’s raw, almost-overwhelming cameo; the quiet chemistry between Mr. Cruise and Jennifer Connelly; the star-making turn from Glen Powell; that fist-pumping finale which somehow manages to Make Jingoism Moving Again…this is the stuff of which iconic crowd-pleasers are made. Your dad will be watching this one for a long time to come. – R.J.

17 | Apollo 10 1/2: A Space Age Childhood

2022 was the year of coming of age films, and if there is one filmmaker who can knock out a period coming of age film, it’s Richard Linklater. With a hilarious narration from the great Jack Black and the beautiful use of rotoscope animation, Linklater has crafted his best film since Boyhood and reminded us all of the joys of childhood. It’s rare to see a film so lived in and unafraid to sit with its characters. This is a universal film, a master transcending the form to invoke nostalgia in any viewer and remind us of the power of the movies. – C.W.

16 | Triangle of Sadness

Triangle of Sadness has received its fair share of criticism for being overly obvious and lazy as a satire of wealth and privilege, and while I’ll grant that the film’s social commentary doesn’t really break any new ground, these critiques seem to overlook one very important facet regarding Ruben Östlund’s Palme d’Or winner: it is very, very funny. I can think of no cinematic experience this year (barring perhaps the equally riotous Jackass Forever) which left myself and the rest of theater laughing quite so hard as the downright glorious second act of this film; Woody Harrelson’s long-delayed arrival into the chaos of the shipwreck sequence lives up to and surpasses any possible expectations, and Östlund’s deft hand behind the camera does an absolutely spectacular job of uneasily, hilariously depicting the ship’s gradual descent into madness (and eventually the ocean). And of course, Dolly De Leon’s breakout turn as a janitor-turned-commune-dictator is also among the more memorable characterizations of the year. – R.J.

15 | Petite Maman

This one is trippy, even more than the blue people movie. A Grieving mom and her young daughter chill at her childhood home but only for the daughter to go back in time and chill with the mom but when the mom was a child like ??? This is crazy! Beautiful performances and a genuinely poignant depiction of familial loss and mother/daughter relationship. There is no cinematic moment more tender from 2022 than Lily feeding her grieving mother snacks and juice from the backseat of the car as the mother begins to smile. Between Petite Maman and her script for Paris, 13th District (which narrowly missed this list), Celine Sciamma has cemented herself as one of the great French filmmakers of today and will most certainly go down in history as one of the greatest filmmakers of our time. – C.W.

14 | Armageddon Time

Deeply moving and beautifully specific, Armageddon Time continues James Gray’s streak of sadly underappreciated masterworks. Banks Repeta gives one of the best child performances of recent years (his soulfulness and convincing naivete far outshining the grade-school autofictional inserts of Belfast and The Fabelmans), and the central trio of authority figures all provide turns that rank among the best of their career. Hopkins’ performance as the family patriarch, in particular, absolutely rips my heart out — the scene in which he regales Repeta with stories of the persecution faced by his mother ranks among the high points of the year. Gray is also pretty enormously successful in his social commentary here; this is essentially the exact inverse of a “white savior” narrative, and while the ultimate nihilism of its climax might leave some cold, it rings far truer than a more typical after-school parable of racial harmony might. Couple this thorny, skillfully-handled thematic territory with Gray’s always-mighty hand behind the camera, and you have what should’ve easily been a major Oscar frontrunner. – R.J.

13 | Thirteen Lives

Angels and Demons, the second film in the Robert Langdon cycle, doubles as a fair descriptor of Ron Howard’s filmography. In the former category, we have such paragons as Parenthood. In the latter, misfires like The Dilemma. It’s a dichotomy that still persists in the 2020s. This is a man who is as comfortable making a film that could (and would) elect a complete deplorable to public office as he is one about the heroic, miraculous, and decidedly uncontroversial (unless your name rhymes with Pelon Tusk, that is) Thai cave rescue.WIth an Eastwoodian simplicity, Thirteen Lives is as unobtrusive and minimalist as Hillbilly Elegy is histrionic and overwrought, focusing on the practical tangibles that enabled diving experts to save the ensconced cave children. Effortless performances from Viggo Mortensen, Joel Edgerton, and Colin Farrell and harrowing, underwater photography bolster an unfussy, small-scale epic. – J.S.

12 | Decision to Leave

It’s a small wonder that two romance films masquerading as other genres would end up next to each other on a year end list, with Park Chan-wook’s Decision to Leave using the conventions of thriller and police procedural to throw us off the trail. One could even go so far as to invoke Hitchcock with its plot, one of Detective Hae-joon investigating the death of a man killed by falling off a mountain he hiked regularly, eventually leading to Seo-rae, the man’s wife, as the prime suspect. Played by Park Hae-il and Tang Wei respectively, the main leads simmer with energy as suspicions grow and investigations twist and turn, never allowing us a clear indication of the truth of either the case or blossoming love, as Hae-joon chips away at both. If the premise has yet to grab you, then the characteristic flourishes and slick editing as the film moves deftly through its mystery surely can, as Park demonstrates the classics as well as a few new tricks in the editing bay. Interestingly, Decision to Leave is also the tamest, in terms of graphic content, in the director’s filmography while still crafting the same captivating experience all the way to an ending that stays with you long after. – N.A.

11 | Bones and All

With 2018’s riveting remake of Suspiria, Luca Guadagnino carved out his own little niche of arthouse horror, one to which he returned this year for the difficult-to-define film Bones and All. As heartfelt as it is shocking, the film follows a flustered, cannibalistic Maren, deftly played by Taylor Russell, as she wanders the country’s backroads and small towns in search of her mother and any inkling of how she came to be the way she is. Along the way, she meets others who share an affinity for flesh, from cannibal guide and eventual lover Lee, portrayed by indie darling Timothée Chalamet, to the eerie old-timer Sully, a contender for most unsettling performance of the year from Mark Rylance, all distinct in their reasons and with each actor bringing such a lived-in quality to their characters that it’s easy to imagine the horrors they’ve seen and even perpetrated in addition to the glimpses shown on screen.

The film itself defies simple categorization, with obvious hallmarks of horror, the wanderings of road films, a hearty dose of coming-of-age anxieties, and even some queer subtext thrown in for good measure. The greater connecting tissue is an ode to the outsider trying to find their place in a world that makes no sense to them, even outright rejecting them for things they have no control over. The Reagan’s America of the film is rife with dangers, both societal and tangible, for our protagonists, but there’s still plenty of beauty to be found, especially with the all-consuming love they share between them. – N.A.

10 | Crimes of the Future

Cronenberg’s most vital work since the stunningly underrated premonition of Existenz, Crimes of the Future finds David reuniting with that most unlikely of muses, Viggo Mortensen (giving a masterclass in physical performance and presence here), and for the first time plunging him into the genre with which he is most infamously associated, the body horror. Indeed, if nothing else, the film operates as his most literal depiction of body horror yet. In some ways he’s playing the hits (Videodrome chussy comes back in a big way), but the film also finds Cronenberg exploring new variations on familiar themes. With its deconstruction of art for art’s sake, Crimes of the Future establishes itself as 2022’s most visceral work of autofiction. And the ending, a sublime homage to The Passion of Joan of Arc, is the most transcendent of the year. – J.S.

9 | Vortex

2022’s most pessimistic film comes from the sinister mind of Gaspar Noe with his new film Vortex. Starring the great Francoise Lebrun and Dario Argento, Vortex tells the story of the final chapter of an elderly couple plagued with dementia. Noe’s use of split screen is brilliant, transcending the gimmick criticism through its consistency and genuine service to the story. Never has the filmmaker been more honest and naked in tone and style; Vortex is Noe at his most mature and contemplative. This is a harsh film, one that puts its audience through a grueling 142 minutes of spousal fighting, misunderstanding, and death. Death of the physical but also the death of love. No film this year approached the concept of death as honestly and fearfully as this film. Vortex is truly Noe’s first masterpiece. – C.W.

8 | After Yang

A superior followup to the already-impressive Columbus, After Yang finds director Kogonada expanding his astounding pictorial talents into the realm of science-fiction without ever losing the warm characterizations and emotional storytelling of his wonderful debut. His gentle, almost-ASMR-ish approach to filmmaking finds a perfect match in Colin Farrell’s quiet but deeply moving performance, and the sensitive turns from Justin H. Min and Haley Lu Richardson round out this fabulous AI fable of memory and the passage of time. – R.J.

7 | Everything Everywhere All at Once

The Daniels’ multiverse-spanning saga of dildos, everything bagels, and Asian-American assimilation was one of the year’s biggest surprise hits, proving that a low-budget indie with a diverse cast and a whopping 7-man visual effects team could still make bank at the box office and earn raving accolades from highbrow critics and mass audiences alike. Michelle Yeoh’s late-career star turn has earned her a sizable amount of overdue praise, but I was perhaps even more bowled over by Ke Huy Quan’s long-awaited return to the screen — his performance as Waymond provides the film’s crucial beating heart, and there’s a reason his climactic romantic plea about laundry and taxes is already nearly a cliche. The Daniels’ visual imagination also proves near-unmatched; it feels as though they took every last bonkers cinematic idea they ever wanted to see onscreen and tried to see if they could stuff them into one movie. The fact that they not only succeeded but also made something that connected with such a staggeringly large audience proves their immense talent. Let’s hope their next project isn’t a superhero movie. – R.J.

6 | RRR

There’s a trend in modern action filmmaking embracing the sleek, calculated, and grounded in their own version of reality, eschewing the bombastic spectacle of the past for something much more clean and easier on the ol’ suspension of disbelief. It is this current trend that RRR, an Indian Telugu-language epic, flies in the face of, aiding it to become an international phenomenon when it released earlier this year (becoming so globally renowned as to earn its own Google easter egg). Its over three hour runtime is rife with bombastic set pieces, over-the-top violence, and feats of strength, patriotism, and above all friendship. On a more base level, the film is a historical epic set during the British rule of India that follows a British officer rising through the ranks, a village protector sent to find a girl abducted by the British governor, and the pair’s friendship that grows as neither knows the truth. The stakes are high throughout as perils abound under the unquestioningly evil British rule, and our intrepid heroes must navigate to their separate goals, amidst chases, romances, conquering nature, and one of the most joyful musical numbers upstaging authority since Footloose. The true joy of RRR lies in the sincerity in which all these incredible sequences are executed, unabashedly reveling in the outrageousness of what’s unfolding on-screen. In true masala film fashion, you get everything you could want and more, but at this fever-pitch, it’s no wonder this film caught the hearts of the world on fire. – N.A.

5 | Avatar: The Way of Water

The long awaited sequel to the most financially successful film of all time finally arrived in 2022, and its arrival could not be more timely. As thousands of Ukranian men and women continue to fight against the tyrannical Russian government, Cameron tells a story of a different type of blue warrior. While one might not immediately connect the Navi of Pandora’s struggle with our Ukrainian brothers and sisters; they both fight for the same cause: home. And what a beautiful home it is. Cameron has crafted what might be the most visually stunning blockbuster of all time. Beautiful ocean scenery combined with stunning 3D and HFR technology comes together to make one of the most powerful cinematic experiences of the year. As the humans butcher the sacred Tulkan and drain the resources of Pandora, the Navi bind together to defend their land. The parallel between Ukraine and Pandora crystalizes in the film’s final moments when Jake Sully, not unlike President Volodymr Zelensky, stands his ground and assures the audience he will make his stand here in Pandora. The future is unknown for both the Navi and Ukrainians, but one thing is certain: they will fight for their home. – C.W.

4 | The Banshees of Inisherin

Stepping away from his usual menageries of hitmen, psychopaths, and powder-kegs, Martin McDonagh focused on the smaller, but no less impactful side of existentialism with this year’s Banshees of Inisherin. Set in the country-side of early 20th century Ireland, the premise is simple enough. Brendan Gleeson’s Colm decides to unceremoniously dissolve a years-long friendship with Colin Farrell’s Pádraic, now left to puzzle over and attempt to rekindle the relationship, which quickly escalates in true McDonagh fashion, turning a one-sided feud into an inquiry on what will have truly mattered at the end of it all.

Citing the visuals of John Ford as a chief influence, regular McDonagh collaborator Ben Davis photographs the foggy countryside of the fictional Inisherin that highlights the ever-present coldness these characters inhabit and the divides between them. Of course, this distance is bolstered by a stellar cast consisting of the excellent Gleeson and Farrell, reunited for the first time since In Bruges and not missing a step, Kerry Condon as Pádraic’s concerned, but just as melancholy, sister and Barry Keoghan as the deceptively foolish Dominic. As bleak as it all sounds, Banshees thrives in its tragic comedy, delivering just the right amount of both to keep one invested until the next revelation, observation, or glimmer of humanity up to the final shot, leaving the us with plenty to think on and discuss with the friends we’ve still got, at least for the time being. -N.A.

3 | Tár

I can’t really think of another movie that moves or shakes quite like this one — the closest analogue would be European arthouse character pieces like Toni Erdmann or Personal Shopper, but the completely unpredictable structure and absurdly detailed world-building of Tár don’t really have another analogue in modern film. I’ve seen several people make comparisons between this film and the works of Stanley Kubrick, and while I don’t agree stylistically, I can see what they mean just in the sense of Field’s sheer directorial assuredness. He is going boldly in his own direction, managing to pull you right along with him by means of little more than his confidence. Well, his confidence and, of course, Cate Blanchett who never once ceases being incredibly compelling over the course of the film’s hysterically long 160-minute runtime and has quite possibly never been better. Could the film be a little shorter? Possibly. Does that Juilliard student referring to themself as “a BIPOC pangender person” feel a bit phony and needlessly reactionary? Perhaps. Nevertheless, Lydia Tár herself remains among the most memorable characters 21st century cinema has had to offer us, and Field’s immaculate stylistic construction easily ranks among this year’s finest feats of filmmaking. – R.J.

2 | Elvis

Elvis is more than a film. It’s a monument. It’s a monument to its director Baz Luhrmann whose distinctive, frenetic editing, ostentatious production design, and anachronistic musical proclivities all service the material here in his most carefully balanced film yet. He takes the canny choice of situating the film through Colonel Tom Parker’s perspective (a comically grotesque performance from Tom Hanks that rivals Butler’s for sheer panache) that also doubles as a filmic avatar for Luhrmann’s status as a showman. It’s a monument to star Austin Butler, who earns his keep with every hip gyration, chorus-belting, and Southern-inflected line reading he performs. When they reference A Star is Born, it’s hard not to make the connection. And, of course, it’s a monument to the King himself who is one of those few figures in American history who seems to be a synecdoche of America itself. Elvis is a film that takes Elvis’ iconic status on these Herculean terms and through spiritual, rather than historical, fidelity gets to the heart and soul of Elvis Aaron Presley. – J.S.

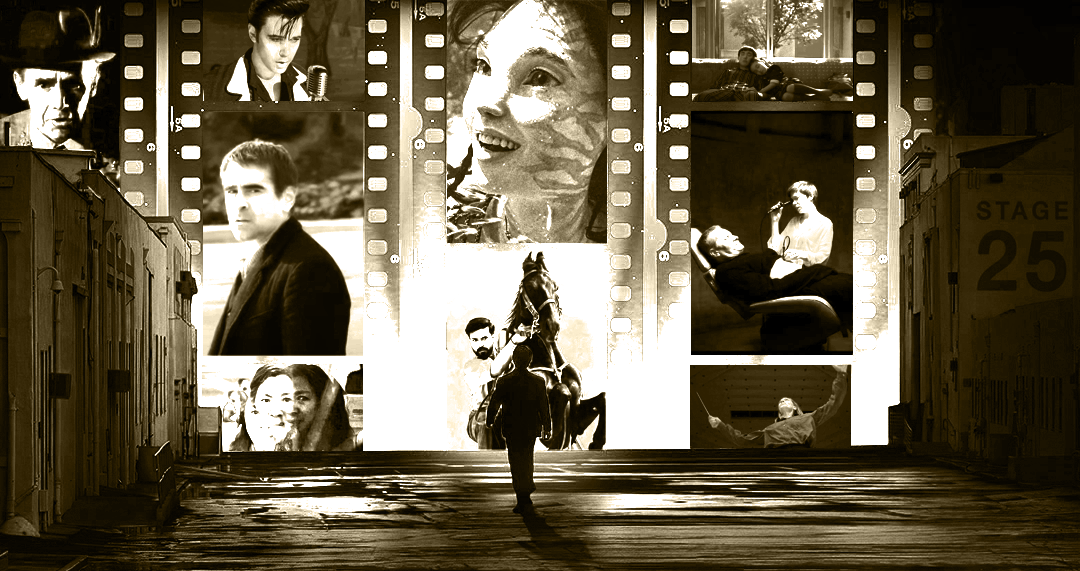

1 | The Fabelmans

There is perhaps no name in the history of popular cinema more synonymous with moving pictures than Steven Spielberg. From his early invention of the modern blockbuster to his 21st century historic masterpieces: Spielberg has continuously proven himself to be the most visually talented and confident filmmaker of all time. With The Fabelmans, Spielberg has produced his magnum opus. A film that is unapologetically personal and unafraid to confront the ethical conflict of what it means to be an artist. Family has always been present in Spielberg’s cinema — who can forget the heartbreaking portrayal of divorce in E.T. or the critical conflict the protagonist of Munich faces as he works to serve both country and family. What separates The Fabelmans from any other Spielberg project is the exploitation on how cinema’s inherent manipulation of human beings impacts how said beings are perceived by audiences. The ordinary fellow boy scout becomes the badass sheriff. The conflicted mother becomes the embodiment of sexuality. The anti-semitic bully becomes an olympic god of human strength and beauty. The power of movies has never been more subtly examined in mainstream cinema and Spielberg unpacks his own perverse pleasure in cinematic manipulation. “Life’s nothing like the movies” is a truth Spielberg has finally accepted and results in the year’s most challenging and profound film.

God bless Steven Spielberg. – C.W.